Former Nintendo employees shed light on the intriguing differences between Kirby's American and original Japanese appearances. This article explores why Kirby's marketing shifted for Western audiences and delves into Nintendo's evolving global localization approach.

"Angry Kirby": A Western Makeover

Nintendo's Strategic Rebranding of Kirby

Fans dubbed him "Angry Kirby," a reflection of the tougher, fiercer image presented on Western game covers and artwork. In a January 16, 2025, Polygon interview, former Nintendo Localization Director Leslie Swan explained the reasoning behind this change. Swan clarified that the intent wasn't to portray anger, but rather determination. She noted the popularity of cute characters across all ages in Japan, contrasting it with the preference for tougher characters among American tween and teen boys.

Kirby: Triple Deluxe Director Shinya Kumazaki corroborated this in a 2014 GameSpot interview, stating that while cute Kirby resonates most in Japan, a "strong, tough Kirby battling hard" appeals more to US audiences. However, he also pointed out that this varied by title, citing Kirby Super Star Ultra's tougher Kirby on both US and Japanese box art. He emphasized the aim to showcase Kirby's serious side through gameplay while acknowledging the enduring appeal of his cuteness in the Japanese market.

Marketing Kirby as the "Super Tuff Pink Puff"

Nintendo's marketing strategy aimed to broaden Kirby's appeal, particularly among boys. This led to the "Super Tuff Pink Puff" branding for Kirby Super Star Ultra on the Nintendo DS in 2008. Former Nintendo of America Public Relations Manager Krysta Yang explained that Nintendo sought to shed its "kiddie" image during that era. She highlighted the pressure to achieve a more "adult/cool" factor in gaming, emphasizing that the "kiddie" label was detrimental.

Nintendo consciously portrayed Kirby as tougher, emphasizing the combat aspects of his games to avoid a purely "young kids" perception. In recent years, the focus has shifted from Kirby's personality to gameplay and abilities, as seen in the 2022 marketing for Kirby and the Forgotten Land. Yang acknowledged the ongoing effort to create a more well-rounded Kirby character, but noted the persistence of his "cute" image over "tough."

Nintendo's US Localization of Kirby

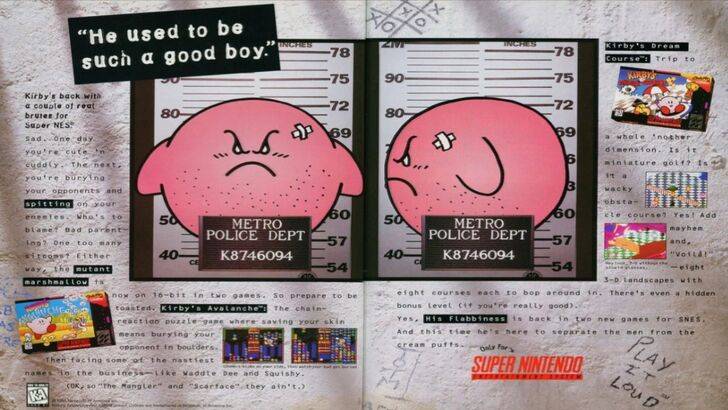

The divergence in Kirby's localization began with a memorable 1995 "Play It Loud" campaign ad featuring Kirby in a mugshot. Subsequent years saw variations in Kirby's facial expressions on game box art. Games like Kirby: Nightmare in Dream Land (2002), Kirby Air Ride (2003), and Kirby: Squeak Squad (2006) featured Kirby with sharper eyebrows and more intense expressions.

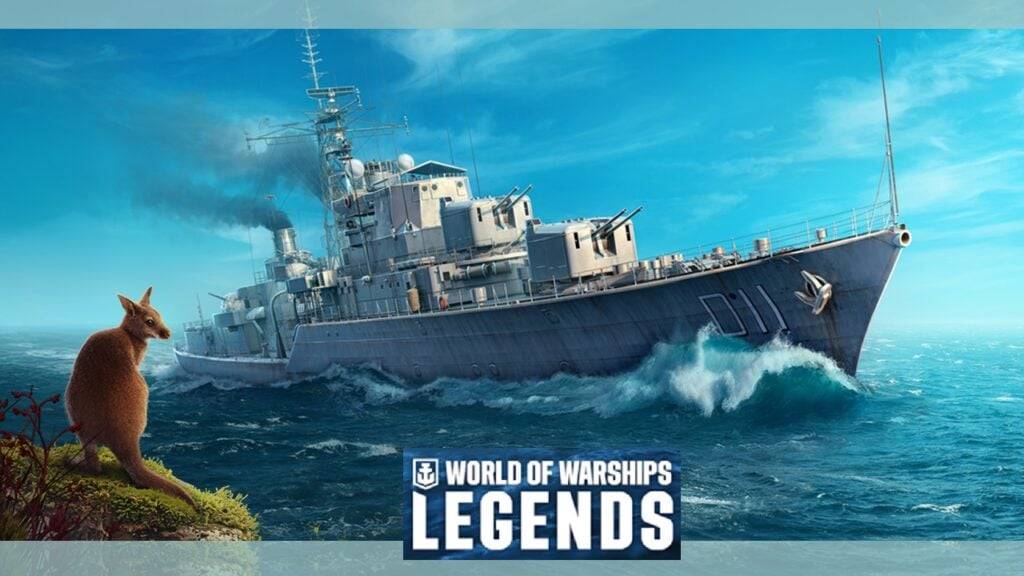

However, facial expression wasn't the only adjustment. The 1992 Game Boy release of Kirby's Dream Land, the first in the series, presented Kirby in a ghostly-white tone in the US, unlike his pink hue in the Japanese version. The Game Boy's monochrome display meant US players only saw Kirby's true pink color with the 1993 NES release of Kirby's Adventure. Swan explained the resulting challenge: a "puffy pink character" wasn't perceived as commercially viable for a broader, particularly male, audience.

This led Nintendo of America to alter Kirby's facial expressions on US box art to appeal to a wider market. Recently, global Kirby advertising has become more consistent, alternating between serious and gleeful expressions.

Nintendo's Global Approach

Swan and Yang concur that Nintendo has adopted a more global perspective. Closer collaboration between Nintendo of America and its Japanese counterpart has resulted in more consistent marketing and localization. The company is moving away from regional variations like differing Kirby box art and avoiding past situations such as the 1995 "Play It Loud" advertisement.

Yang noted that while the global audience remains unchanged, the business strategy shifted towards global marketing. She acknowledged both advantages and disadvantages: global consistency benefits branding, but it can also lead to a disregard for regional nuances, potentially resulting in "bland, safe marketing." This trend, she suggests, is partly due to industry globalization and the increasing interconnectedness of audiences, with Western audiences now more familiar with Japanese culture.